Guest posting by Sharon Syau

During the first semester of biochemistry, my classmates and I learned the details of the Kreb’s cycle—a process responsible for turning half a sugar molecule into cellular energy, or ATP. Honestly, I was feeling pretty good when the semester wrapped up.

Then the second semester came around, and I found out (much to my dismay, since break had allowed my hard-earned Kreb’s cycle knowledge to slip away) that every other macromolecule seemed to feed into or come out of some other molecule in the main loop of the Kreb’s cycle. For an idea of what the pathways are like, click here; for a dramatized version of my reaction, click here.

I bring this up because thinking about the interconnectedness of the body’s metabolic pathways is very much like thinking about patient engagement.

In trying to map the elements that influence patient engagement, I found that the big ideas we had identified were connected, and that the levels of elements like trust or assurance could regulate the amount or quality of communication between the patient and the doctor. At the same time, however, assurance itself relies on both communication (assurance needs to be communicated) and some existing trust (assurance from an untrustworthy someone is not assuring at all), so we find ourselves with a chicken-or-the-egg problem.

Using metabolic pathways as a framework, though, gets us away from looking for single starting point for our problem. To break down sugar, we need not just the glucose, but a host of other enzymes and molecules as well. In a similar vein, my group and I have come to realize over the course of the semester that all of these elements—trust, assurance, and communication—need to be present to help increase a patient’s voice during a patient-doctor interaction, and that each of them modulates the others.

While I’ve modeled patient engagement as a pathway that requires several coexisting elements and careful regulation, what I’ve really drawn is something very similar to the Kreb’s cycle from the first half of biochem. My diagram outlines the big ideas that my teammates and I have identified, but it does so largely from the patient’s perspective.

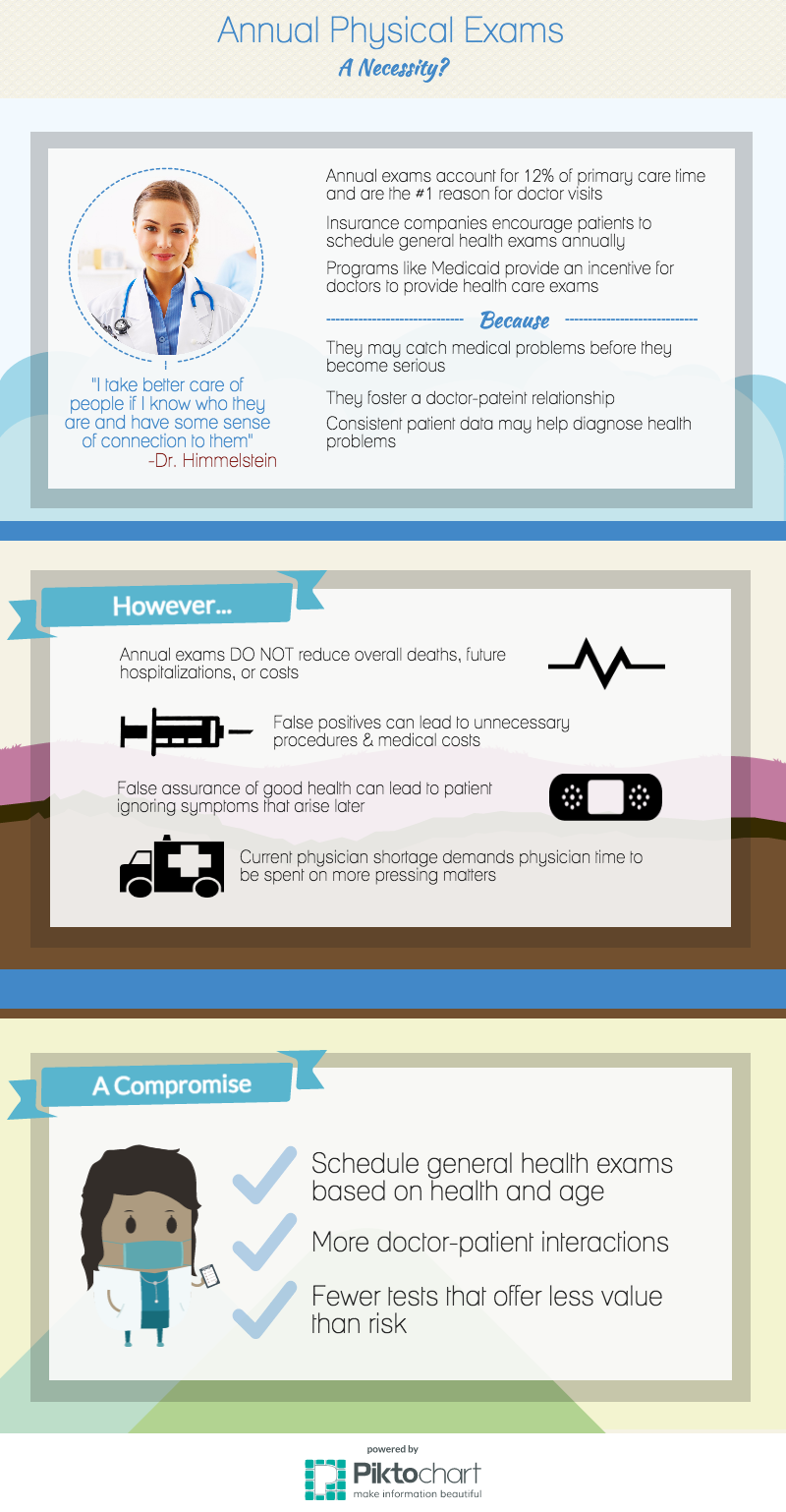

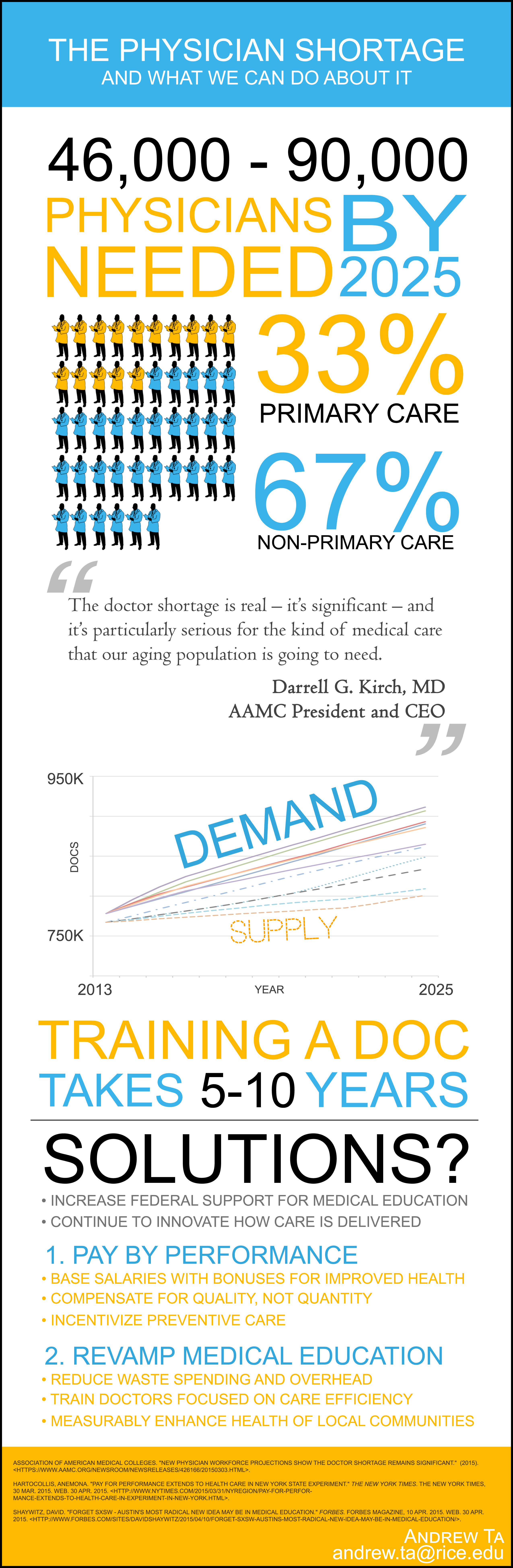

If my diagram is the Kreb’s cycle, then we can think of the healthcare system as the organism. Nurses, physician assistants, hospital administrators, insurance companies, pharmaceutical companies, and government agencies all have a stake in the way healthcare works. Each of these stakeholders feeds into patient care at some point, but each is also a distinct pathway, subject to other methods of regulation.

Though this complexity is daunting, it isn’t impossible to map, understand, and eventually change. Just as modern medicine has developed drugs that tinker with our physiologies, so too can we, with enough research, optimize the way healthcare works.