A joke I’ve often heard before is about engineers and their inability to actually design apps. The gist is that the engineers have large amounts of creativity and technical expertise and can create amazing devices, but the actual interface is designed terribly. Now, obviously this isn’t the case in real life: engineers are just as good as the general population in general interface design properties, if not better. The problem is that, to make a good interface, one needs to put in some serious research and effort. I learned from a human factors class that, when you design something, you want it to be so good that your consumers don’t realize that there could be any other design.

One important factor to note is that the device in which the interface is used on is extremely important to understanding the design. Earlier in the year, my design team tossed around ideas about some sort of web app or website, so I looked around a little on the internet and learned about WIMPs

But not that kind of wimp. WIMP http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WIMP_(computing) is a term in human-computer interaction which stands for “windows, icons, menus, pointer.” These are elements that are—or were—supposed to be used in user interfaces, and have been in place for a few decades now. WIMP interfaces have:

- Window: a usually rectangular area which runs a self-contained program or application.

- Icon: A symbol used as a shortcut that represents and execute an action or run an application

- Menu: A list or sets of lists that allow a user to select and execute programs and tasks, and are often in “pull-down menu” format.

- Pointer: an onscreen navigation symbol that allows a user to select things.

All these seem very basic right? You’re probably reading this post on a computer that uses these elements as part of the UI, on an internet browser that also uses a WIMP-style GUI (Graphical User Interface). In fact, but a decade ago, this was the dominant form of UI design. As I mentioned before, the thought was generally “Well of course you design an interface that way. How else could you design it?!” Later, we got the iPod, which was one of the major players in moving away from this system due to the lack of true windows (the iPod used different screens instead of discrete windows), icons (text was used), and pointer (no actual pointer, but the blue “select” option served the same purpose). Now, we have interfaces that no longer require WIMP-style interfaces: touchscreen devices, augmented or virtual reality systems, and voice or gesture based systems. They are considered post-WIMP interfaces and rely on different types of design elements.

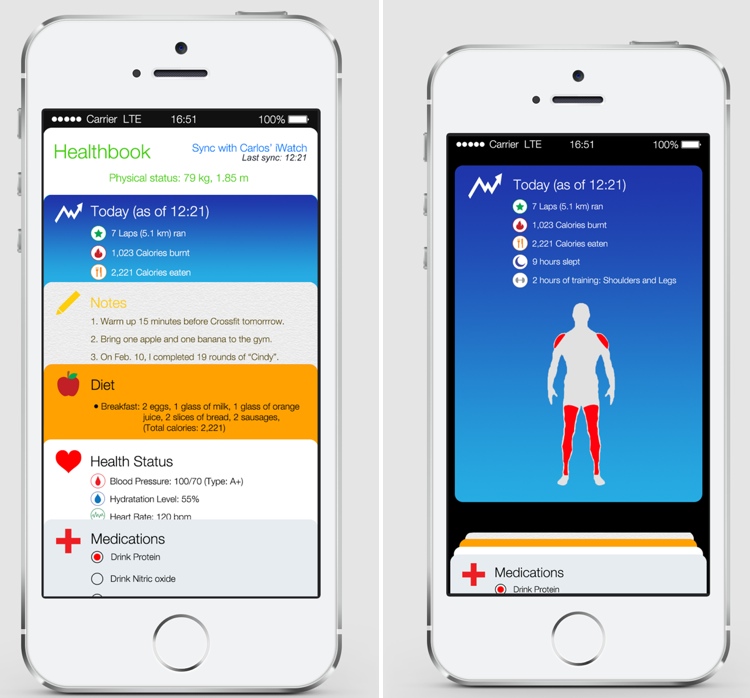

I’m going to come back to this topic: I find it useful for anybody that wants to design a product or companion for some kind of service. For now, though, I just want to leave with this: the design elements of a device must be considered carefully. Not only do computers have different design strategies than mobile devices, but the design strategies will differ between iOS, Android, and Windows apps. With this in mind a little research on design will prove fruitful.