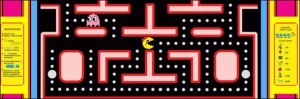

I probably play too many video games. What can I say? They’re fun! Game developers try to make their games more fun (and get more money) by employing a range of psychological techniques that not many people are very aware of. Even early arcade-style games tried to keep kids playing and paying with public leaderboards and unforgiving mechanics. What I mean to show with these examples is that game developers are really good at shaping people’s behaviors.

But let’s talk about healthcare for a moment. Our class just finished with a critique of our projects, and all the groups had really great ideas. I talked with Fred Trotter (@fredtrotter) afterwards, and he mentioned to me that what my group—as well as most of the other groups—is trying to do at its core is to change someone’s behavior.

That’s where the game design ideas came in. Actually, a couple groups already had the idea to try to heal patients by making some sort of game. They were trying to gamify healthcare.

Gamification. There’s a buzzword if I’ve ever seen one. Gamification means to apply game design techniques to non-games for some sort of benefit. Thus far, it seems to have been pretty successful in the fitness area with things like Nike+, Fitocracy, Runkeeper, or Zombies, Run! Unfortunately, this Gamification phenomenon is really new—according to Google Trends, it just popped up around mid to late 2010. As a result, there isn’t a lot of information about how it can be used best in the medical field.

So what would it take to gamify healthcare? Seems like you could just add a few badges for keeping your blood glucose low or something, right? Well, turns out it’s a lot more complicated than that. People have tried to gamify many things and failed because of inadequate design practices. Enterprise Gamification consultancy is a great resource to learn more about what works and doesn’t, but there seem to be a couple useful tricks and tips.

The general idea is that people tend to have a desire for competition, achievement, and altruism, all of which can be used to drive action. These desires are not mutually exclusive: projects like Foldit have crowdsourced problems by having players compete with each other to earn a high score while simultaneously helping solve protein tertiary structures for research. Other games have RPG-style experience curves, allowing a player to enjoy an initial, gratifying “level-up,” which later takes more time but still holds the promise of some reward. Some use a “variable ratio” reward schedule in giving some sort of reward after a random amount of trials (which sometimes results in addict-like behaviors, read: gambling).

My point in all this is that gamification, while it can be great for changing behaviors, can be hard to do without some knowledge of psychology and sociology. That said, I don’t see it going away any time soon. Quite the opposite; once people know how to use these techniques to their advantage more frequently and in the context of healthcare, I’m sure we will be seeing a more gamified—and healthier—country in no time.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I’ve got to get back to killing marsh rats on my Orc Warrior.