Guest post by Olivia Banner.

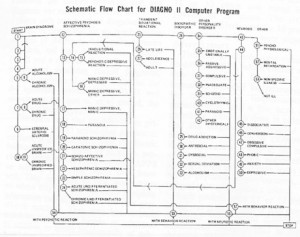

“Schematic Flow Chart for DIAGNO II Computer Program,” Robert Spitzer and Jean Endicott, American Journal of Psychiatry 125, 7 (1969): 15.

In a previous post, I wrote about Ted Gup’s critique of the current rush to organize human differences into diagnostic categories, which he published on the heels of the CDC’s recent report that 11% of U.S. children are currently diagnosed with ADHD (see “Diagnosis: Human”). It’s interesting to consider this critique in light of the DSM’s history, and in light of projects to automate diagnoses using computers, all of which produces some intriguing questions about the future of EMRs.

Some readers may already be familiar with the vagaries of how the DSM has treated “homosexuality” over the years: it wasn’t until 1986 that editors completely removed it from the DSM.

This is only one among many examples of how the DSM mirrors cultural attitudes toward the groups of “symptoms” it classifies as psychiatric disorders.

In the late 1960s, one of the DSM’s previous editors, Robert Spitzer, developed a computer program intended to automate diagnosis. Called DIAGNO, the program was envisioned for use during intake at psychiatric facilities. Spitzer’s basic premise was that, since clinicians employ a decision tree to arrive at a differential diagnosis, and software code also uses decision trees, a computer program could be equally if not more precise than humans at determining diagnoses. DIAGNO went through three versions as Spitzer fine-tuned it over the years, aiming for a program that could one day skip the clinical encounter altogether.

As far as I’ve been able to figure out, DIAGNO remained a dream that was never implemented; however, it’s interesting to note that Spitzer was building on other researchers’ programs to automate recommendations for which drugs to use to medicate specific disorders. One of these was used in the late sixties at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston. (Please comment if you have any additional information on DIAGNO’s implementation!) The dream of automating diagnoses lives on, however, whether in technologies intended for use in the home such as SCANADU, which would diagnose medical conditions, or those for use in clinical settings. In the latter category we could include a fascinating project that attempts to integrate findings from cognitive science to help automate psychiatric diagnoses, so that diagnoses can be reached through a computer program analysis of a patient’s narrative (see Cohen et al., “Simulating Expert Comprehension”).

I wonder what Ted Gup would say about this latter effort. In this dream of a future where diagnoses are automated, his narrative about his suffering might, when analyzed by software, be diagnosed as a condition suitable for treatment. Do we want this future where computers can diagnose? What happens when EMRs are based on diagnostic categories that can’t reflect the particular exigencies of their historical moment that drive the diagnosis?

How does automating diagnoses occlude broader cultural debates about the diagnoses themselves? And how can we, as educators, best alert our students to these problems, even as we search for more efficient ways to implement new digital technologies into clinical practice?

![See page for author [GPL (http://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl.html) or Attribution], via Wikimedia Commons 512px-Electronic_medical_record](http://www.medicalfutureslab.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/512px-Electronic_medical_record-300x216.jpg)

![By Bryson Jack, Ministry of Information Photo Division Photographer [Public domain or Public domain], <a href="http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ABlood_Drying_Unit-_Processing_Blood_in_the_Laboratory%2C_Cambridge%2C_England%2C_UK%2C_1943_D16766.jpg">via Wikimedia Commons</a> Blood_Drying_Unit-_Processing_Blood_in_the_Laboratory,_Cambridge,_England,_UK,_1943_D16766](http://www.medicalfutureslab.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Blood_Drying_Unit-_Processing_Blood_in_the_Laboratory_Cambridge_England_UK_1943_D16766.jpg)